Luisa Isidro-Herrera

“In Colombia, children and adolescents have been significantly affected by armed conflict… Pedagogical efforts by teachers to break these silences and the cycles of violence they foster have created the tool of the circular landscape of memory.”

“I never imagined the audience I would find. There were kids 7 to 10 years old asking serious questions about women in guerrillas” (Informal conversation, University of Amazonia, Caquetá, June 2022). This was shared with me by a teacher in Caqueta, who expressed her concern to me when she learned how young the participants in their forced recruitment workshop were and what questions they asked. This teacher is currently part of the Caquetá Teachers Network, which employs the encrypted memories methodology to unpack how the armed conflict affects both children and adolescents.

According to the recent report No es un mal menor by the Colombian Truth Commission, between 1986 and 2021, children and youth faced human rights violations including: enforced recruitment; enforced displacement; homicide of their parents; enforced disappearance and kidnapping; capture of their educational facilities by armed groups; unsatisfied basic needs, among others. In response to these violations, rural school teachers in Caquetá organised through their Teachers Network to tackle violence in their school environments.

In this blog post, I contribute to the themes of leadership and changing mindsets in the ‘sustaining peace’ blog series of Civil War Paths, by drawing on my fieldwork experience from 2022 in Caqueta. I highlight how The Caqueta Teachers’ Network uses the circular landscape of memory as a pedagogical tool to defy silent traumatic experiences, create self-consciousness and collective political awareness in children and youth to foster transformative and political change in their schools through the mobilisation of historical memory.

The decryption of memories for the sake of ‘high hopes’

From 2018 to 2022, the Pedagogy Strategy team of the Truth Commission convened educational communities through co-creation labs, the “Que la Verdad sea Dicha“(QLVSD) community and the legacy of the Truth Commission mandate. These initiatives were based on participatory action research methodologies to promote the importance of truth-seeking and truth-telling in schools.

The Caquetá Teachers’ Network developed a pedagogical tool called circular landscape of memory as part of the Historical Memory Education Approach, which identifies and questions the oblivion imposed by traumatic acts on children and youth. This tool utilises the encrypted memories methodology to foster collective memory-building exercises, restorative practices and peace-building in school environments with students. This methodology focuses on how fear, pain, and trauma caused by victimising acts prevents us from telling our own story. The memory of these acts is therefore encrypted and hidden, which prevents the recall of traumatic events. An unwillingness to rely on one’s own testimony is a denied memory, buried under an obliterating layer of oblivion.

The implementation of this pedagogical tool creates spaces of care that provide quality education, sustainable cities, and communities in spite of the hyper militarisation and prolonged armed conflict in this region, empowering children and teenagers to transcend traumatic experiences they have endured due to armed conflict. The tool creates spaces for listening and personal questioning which allows students to de-silence memories in order to build cycles of peace rather than reproduce spaces of pain that follow the enemy-centric approach that armed conflict has left in Caqueta.

Several moments are involved in the creation of the circular landscape of memory. The mandala, which is the opening and closing stage, serves as an icebreaker to create an intimate space. This is where participants share special objects, phrases, elements, smells, songs, and poems that are meaningful to them. In its rhizomatic state, the mandala takes on a shape that is collectively generated. The process is then followed by an encouragement for everyone to expose their own fears and to tell their own stories. During an implementation session of this tool, one participant shared that she was a former member of the National Liberation Army (ELN). The intimacy of this space also encouraged another participant to reveal that two members of their family belong to non-state armed groups: one in the insurgency and one in the counterinsurgency. After more than six decades of armed conflict in these regions, this collective effort to unearth trauma and memory demonstrates how violence and militarization have permeated kinship, and that through generational scales we have all been influenced by the armed conflict.

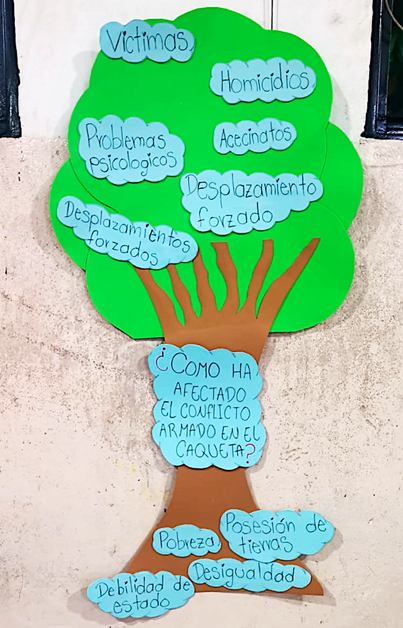

Photo taken by a member of the Caquetá Teachers Network, 2022

Photo taken by a member of the Caquetá Teachers Network, 2022

The remaining stages involve a collective emblematic cartography of significant places within the communities, where violent acts have occurred. Here, students from an institution in Florencia, the capital of Caquetá, created a tree of the victimising acts they felt or suffered. The last stage involves a reflection process to denaturalise violence and its multiple manifestations. This is done to promote coexistence within the impacted territories.

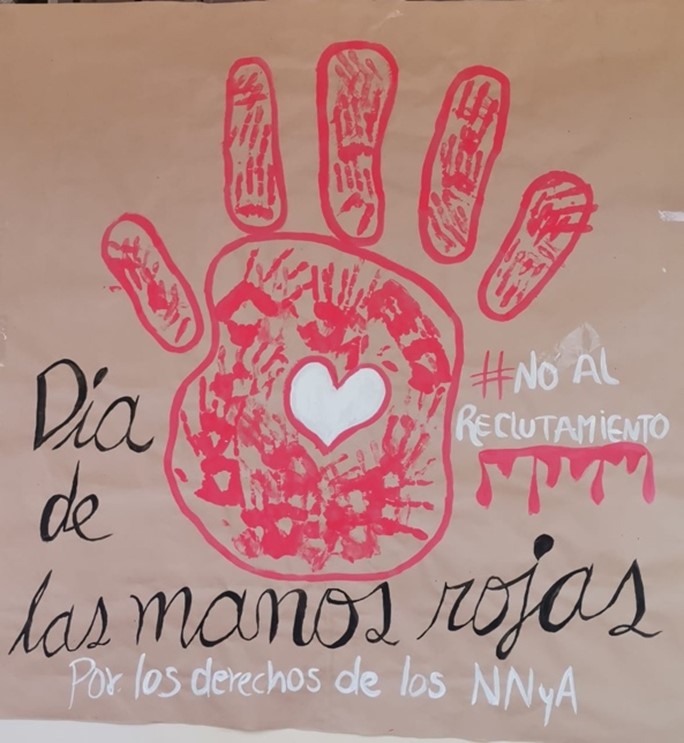

This tool enables participants to recover and re-story agency. In Agua Bonita, Caqueta, I observed how students from the University of Amazonia advocated to implement this tool with former FARC combatants. The stimulation of their historical memory encouraged their interaction in a safe space. Teachers advocating for the use of this tool also hope it will help reduce recruitment into armed groups among children and youth. As a Florencia teacher explained of a student whose brothers were killed by an armed group: “She told me she was thinking of heading to the mountains… I hope the tool will help her decide, but I have high hopes” (Informal conversation, Florencia, Caquetá, June 2022). The tool allowed the students to process their trauma and grief in a safe and secure environment, giving them an opportunity to express their feelings and share their stories. It also provided them with a sense of hope, knowing that their stories could be shared with others and that their feelings would not be dismissed or judged. This allowed them to process their emotions and create a space for them to explore other options, such as not joining an armed group.

Photo taken by a member of the Caquetá Teachers Network, 2022

Photo taken by a member of the Caquetá Teachers Network, 2022

Conclusion

In Colombia, children and adolescents have been significantly affected by armed conflict. Caquetá, in particular, has been a community where silence has been imposed by violence and trauma, in the form of encrypted memories. Pedagogical efforts by teachers to break these silences and the cycles of violence they foster have created the tool of the circular landscape of memory. In its implementation, this tool challenges the silences and violence streams generated intergenerationally among children and adolescents. Through self-acknowledgement of pain and trauma, the tool helps reduce stigma and fear around talking about difficult topics, such as violence. It also raises awareness among young people about how to transform pain into agency and leadership. Their agency is demonstrated by their self-identification as both victims and political actors, as well as their ability to contribute to the transformation of their community and environment, in which they participate by not repeating the acts of violence they have endured. In doing so, their leadership draws on recognition of their rights, violations of their human rights, and the ability to hold complex dialogues with former combatants of the FARC-EP. These dialogues offer hope by creating a sense of connection between youth and their communities and provide spaces for young people to break spirals of violence.

Photo taken by the author, June 2022