Dr Sayra van den Berg

“In South Sudan, the vocabulary of transitional justice has created a language of exclusion.”

This piece is re-posted from the Leuven Transitional Justice Blog, the original blog can be read here.

Despite being the world’s youngest state, South Sudan’s history is storied with war. In 2011 South Sudan became independent but inherited a culture of impunity, violent and extractive governance, and a fragmented rebel movement-turned government. Less than three years later, the world’s newest nation was thrown into civil war once more. The end of South Sudan’s most recent civil war and the signing of the Revitalized Agreement for the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS) peace agreement in 2018 established firm commitments for transitional justice. However, today, the ambitious promises of transitional justice in South Sudan remain unfulfilled, and peace remains fragile.

South Sudan’s (broken) transitional justice promises

Transitional justice measures in South Sudan were first laid out in the 2015 Agreement for the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (ARCSS) peace agreement. In 2018, calls for transitional justice were repeated in Chapter V of the Revitalized Peace Agreement (R-ARCSS), which mandates the establishment of a truth commission – the Commission for Truth, Reconciliation and Healing (CTRH), a Hybrid Court for South Sudan (HCSS), and a Compensation and Reparation Authority (CRA).

Since the signing of the R-ARCSS peace agreement in 2018, a tenuous peace has held in South Sudan, yet the peace agreement’s transitional justice commitments remain largely unfulfilled. To date, the CTRH is the only mechanism that has seen any real movement towards its realization. In 2021 a Technical Committee was established to lead public and stakeholder consultations to inform the legislation establishing the CTRH. In 2022 these consultations took place and a final report was submitted to the government, which, as of the time of writing, has not been made public. Despite these efforts, delays continue to plague the implementation of Chapter V and, to date, none of the R-ARCSS transitional justice mechanisms has become operational.

Recently (in April 2023) a report by the UN Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan described the prevailing climate of impunity and ongoing gross human rights in South Sudan as a ‘central factor in why the country remains trapped in cycles of violence’ (para. 301). The report laments the ‘woefully slow’ (para. 370) pace of transitional justice and calls for the urgent implementation of Chapter V commitments to ‘reverse the culture of impunity’ (para. 299) which has become entrenched and without which a meaningful transition toward peace and democracy ‘will not succeed’ (para. 412).

The arts as unconventional transitional justice spaces

The nexus between the arts and transitional justice is an area of scholarship and engagement that recognizes the transitional justice properties and potential of the arts (photography, dance, music, theatre, literature, painting, public art installations, film, etc.). Work by scholars like Destrooper, Impey, Kouadio and Herremans (together with Destrooper) explores the justice contained within performance, music and literature in contexts ranging from South Sudan, Syria and Cote d’Ivoire.

In South Sudan, an environment characterized by its narrow space for freedom of expression, repressive government controls and plagued by ongoing delays in its formal transitional justice commitments, artist activists are using the arts to carve out creative spaces for reconciliation and resistance.

Mobilizing the arts for reconciliation takes many forms in South Sudan. Public art installations are a popular medium for communicating the need for reconciliation. In 2016, the youth-led arts for peace movement, Anataban, (meaning ‘we are tired’ (of war) in Arabic) led a street art project in which a mural entitled ‘let us all do our part’ was co-created by artists, youth and others in the streets of Juba to bring people together and highlight the need for inclusive peace and development.

Music is another powerful tool of artistic political expression in South Sudan, and several prominent musicians have released pop culture songs on the themes of peace, justice and inclusive nation-building since 2018. Among them is Manasseh Mathiang, an activist musician, whose recent album, Hagiga (meaning ‘truth’), tells the story of South Sudan’s past, present and his hopes for its future, across 12 tracks. The cathartic power of art, as a tool for trauma healing is also being harnessed as a trauma therapy practice within communities. According to one such art trauma therapy practitioner whom I interviewed in Juba in November 2022, “art has the power to unify us, our trauma, guilt and remind us of our connections”.

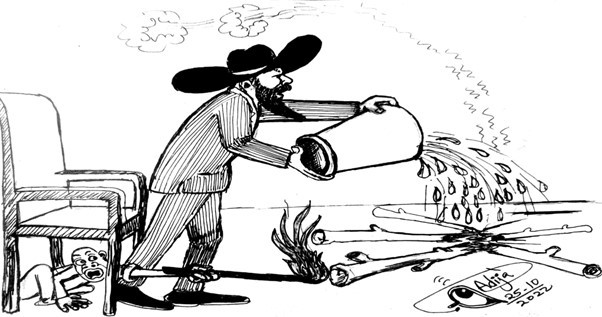

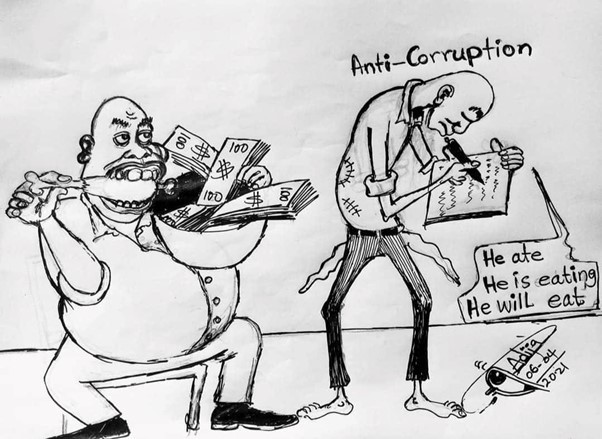

The arts are also being used as tools for memorialization, resistance and accountability in a context where formal accountability structures remain vacuous. In January 2023 South Sudanese musicians collaborated to release a song entitled ‘Disappear’ which pays tribute to the thousands of victims of the 2013 civil war in an artistic expression of memorialization and truth-telling. The country’s bold political cartoon scene also regularly publishes artistic condemnations of government officials, sharing portrayals of corruption and violence to audiences around the country, and globe.

The artist activists within these spaces emphasize the reach of these tools, tight government controls on civil society, and the plural truth-telling that arts enable as critical to their reconciliation, resistance and transformation goals. In a country with over 60 local languages and with one of the lowest literacy rates in the world, the arts are able to tap into and bridge local ecologies of communication across ethnic and educational divides. The power and potential of the arts are thus also uniquely positioned to contribute to recent calls from the UN on the need for deliberate measures to ‘create public awareness and address language barriers’ (377) in the design and implementation of transitional justice processes.

High levels of government control and repression on conventional civil society activities limits their independence and responsiveness, pushing activists toward creative spaces for promoting peace and justice. Finally, the space for plural truth-telling provided by the arts enables competing memories of South Sudan’s disputed histories of violence to co-exist, providing a channel through which to challenge the government’s hegemonic memory of war and peace and therein find community in plurality. Similar to the work of arts professionals like Teodora Ana Mihai in Mexico, the arts in South Sudan have become a tool for translating and communicating personal experiences of war and peace.

The arts as unrecognized transitional justice spaces

The transitional justice goals of reconciliation, truth-telling, resistance, accountability and transformation are deeply embedded within these artistic spaces, making them clear examples of unconventional spaces of transitional justice. Yet, the transitional justice properties of these spaces remain largely unrecognized, by those actively working on advancing the country’s formal transitional justice agenda and the artists themselves whose work embodies these very same transitional justice goals.

In South Sudan, the vocabulary of transitional justice has created a language of exclusion. The narrow focus on pursuing peace by the book (of the R-ARCSS peace agreement) has marginalized creative pathways for justice and transformation and rendered these unconventional transitional justice spaces largely invisible and siloed within South Sudan’s wider ecology of transitional justice. Interviews with artist activists as well as civil society members and government officials working on advancing transitional justice reduce the pursuit of transitional justice within the country to the formal transitional justice mechanisms promised within Chapter V of the R-ARCSS.

The challenges of reach, inclusivity and responsiveness within the design of the CTRH, as the only transitional justice mechanism that currently stands any chance of becoming operational, are the subject of perpetual discussion among transitional justice advocates in civil society who remain oblivious to the meaningful and inclusive transitional justice work of the arts. Similarly, artist activist interviewees are quick to redirect me to the cadre of transitional justice advocates in Juba when the concept of transitional justice is raised. This restrictive vocabulary of transitional justice has thus rendered the transitional justice value of the arts invisible, preventing the possibility of fruitful collaboration by segregating these spaces that share the same goals but whose work toward them remains siloed.