Tiina Hyppä

‘The demise of civil governance in Syria was not a given. At times the councils provided services and tried to build a new state. This experience has been important, and it has created intellectual capital for participants. Many of them are still active, either inside or abroad, working for a future Syrian state and using networks they created in local councils…’

Civil governance in civil wars – governance by civil actors and not by rebel groups – creates opportunities for civilians to manage their affairs and develop alternative systems to those of armed groups. Civil governance faces many challenges, however: it can be undermined by armed groups, or destroyed in war. How do external actors contribute to governance efforts?

In this text I first describe how local councils were formed in opposition-held areas during the Syrian conflict: using findings from my fieldwork, which clarify how spontaneous mobilisation (one of the four ‘pathways’ advanced by the Civil War Paths project) can evolve a more permanent structure. Second, I address the question of external aid, and its impacts on local governance. Foreign actors strengthened the early networks, but not enough to sustain them in the long run. International actors are relevant to the CWP framework, since hardly any civil war remains without external influence (be that funding, arms, or safe spaces for people to flee to). External actors can even have their own visions of how a civil war should evolve. To successfully unpack the various logics of civil wars, I encourage the CWP project to include these actors when analysing the existing pathways.

My research focuses on local councils as civil actors – for which I have interviewed dozens of former council members, and people working with the councils. Most councils were formed in 2012-2013, after the Syrian regime withdrew its forces. The councils’ purpose was, first, to deliver services and, second, to create governance that would represent local people. Councils strove to create the kind of micro-order recently discussed on this blog, on the ground.

Each council evolved in specific ways, and councils were never united under one umbrella. But in general, as Menkhaus demonstrates in the case of Somalia, it was councils that were best placed to provide services – as opposed to regional or national governance structures, or formal opposition bodies based far from people’s daily lives in Turkey. Today, most councils have ended their work in the face of challenging environments. The experiences and networks that were created during the formation period can, however, have a positive impact on Syria’s future.

Old and new networks

Many of those who became council members took to the streets in early 2011. They were part of the spontaneous mass movement explored by Pearlman. Some started to provide relief items for demonstrators or record what was happening – either independently, or as part of Local Coordination Committees, or other revolutionary organizations. These initial ad hoc functions laid the ground for local governance to emerge.

As violence developed, many Syrians fled to their home communities in areas vacated by the regime. For example, students returned from cities to their rural hometowns to continue revolutionary activities. Local council membership often required an individual to be registered locally. Therefore, many who joined local councils were linked through friendships, family, or other social ties. Such earlier social ties enhanced trust between council members.

These networks were not a part of the formal opposition, directed towards regime change. Nonetheless, the main criterion for council membership was revolutionary activity – supporting the revolution against the Assad regime. Technocrats were also valued as the skills of doctors, engineers, or media personnel were needed. This story of local council formation sheds light on the CWP mobilisation pathway: as a mix of spontaneous engagement and earlier societal networks combined to create new possibilities for governance.

Challenges

Local councils benefited from the opportunities associated with prior/new networks. But they also faced enormous challenges. First, even though some councils featured individuals with experience in governance were involved, local governance often had to be built from scratch. Libya post-Qadhafi faced a similar problem: with the collapse of the regime also involving the disintegration of institutions. Creating democracy is hard, but it is especially demanding in the absence of pre-existing systems on which to build (or in the event that participants want to build new systems). Pre-2011 Syrian governance was highly centralised, with local representatives enjoying little legitimacy. The post-2011 goal was to build a new kind of governance.

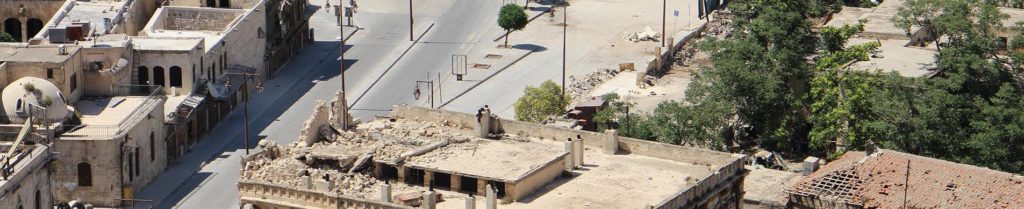

Second, shelling and bombardments effectively destroyed infrastructure needed for service provision; for example roads, schools, or bakeries. Regime violence was perhaps the biggest challenge to civil life and civil governance. Air bombardments and sieges ensured that the regime could retake most opposition-held areas. Many former council members were displaced to Turkish-controlled northern Aleppo, neighbouring countries, or even further from home. Neither local, moderate armed groups nor the international community could (and in the case of the latter, would) protect civil actors enough to make civil governance sustainable.

Third, lack of resources was a consistent challenge for the councils. Often unable to collect local taxes to finance their work, councils were dependent on foreign aid. Several local councils received external aid from (I)NGOs and foreign governments. Between 2011 and 2018 Western countries supported civilian stabilisation efforts and local governance in Syria’s opposition-held areas with roughly one billion dollars. Some better-funded councils used such aid to operate and distribute services. However, aid was not directed equally across all councils. Those who could write better tenders or who were located away from front lines (where relief offered could be quickly lost in bombings) obtained more funding. Such resource inequality posed an obstacle to the civil opposition uniting under one umbrella – those with the resources did not see any benefits of working with other councils or opposition bodies.

Without sufficient resources people with suitable abilities left their work in the council and took on jobs in local or international NGOs in the vast humanitarian field inside or close to Syria. These had resources to pay better salaries, sometimes several times higher than what local councils could afford. This ‘local brain-drain’ reduced the number of able members in the councils, naturally affecting their capacity.

Moreover, councils could not rely on a consistent flow of external aid, since much funding was project-based. Donors themselves have acknowledged this was a problem. Not all projects were completed because of lack of steady management or financial monitoring skills in the councils. Furthermore, much of the funding was lost after radical Islamist armed groups conquered areas and civil governance was not deemed possible. Without resources to deliver services, the councils lost legitimacy in the eyes of the people. Local governance was an easy target for armed group takeover and civil councils had to cease their work. Extremist armed groups obtained more resources from foreign supporters than moderate groups which had allowed civil governance to exist. In the end, the sword was mightier than the pen.

External actors – a fifth path?

The example of local councils shows only one dimension in which external actors can affect civil wars. In many cases external actors were the reason local councils could function, but they also hold responsibility for failures. As Autesserre and Vince have written, international interventions in all conflict-phases should consider local needs in order not to create more harm on the ground. Their effects are not limited to civil governance, but can also influence the onset, course, or ending of civil wars. Because of their importance to the various stages of civil wars, it is worth analysing whether external actors constitute a fifth path in the logic of civil wars.

The demise of civil governance in Syria was not a given. At times the councils provided services and tried to build a new state. This experience has been important, and it has created intellectual capital for participants. Many of them are still active, either inside or abroad, working for a future Syrian state and using networks they created in local councils. It is often said that revolutions do not happen overnight – they can even take decades. Those Syrians with experience of civil governance and democracy will re-emerge in future if new opportunities arise. The international community could help them, if it can learn from past mistakes.