Natalia Tellidou

@NTellidou

“attention to the role of gender framing by conflict actors offers significant opportunities to deepen understandings of when, how and why Western states endorse, support and finance armed groups.”

On February 10, 2015, Nasrin Abdullah, in her role as commander of the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) in Kobani, Syria, discussed the military needs of the YPJ in their fight against ISIS with French president Francois Hollande at the Élysée Palace in Paris and asked for more weapons to support their fight. The YPJ are an integral part of the People’s Defense Units (YPG), Kurdish forces operating in Syria defending and governing territories in North and East Syria. On YouTube, Nasrin Abdullah shared why the fight against ISIS is meaningful: “A place liberated by women becomes a source of morale [hope]. A source of strength. Of equality. It becomes a source of peace.” This visit was successful as France provided weapons and military equipment aiming to defeat ISIS under the U.S.-led operation Inherent Resolve.

While states frequently support conflict actors in civil wars, the legitimacy of such support is often problematic. However, in the case of the YPJ, as demonstrated above, it not only gained legitimacy but also popular support. This raises the question of what role conflict actor ideology, and alignment with Western perceptions of women’s emancipation specifically, plays in legitimising state support for these actors? Does such gender framing influence states willingness to publicly sponsor conflict actors in civil wars, rather than doing so covertly?As Western governments have embraced the gender frame in their fight against terrorism in Syria, could similar narratives allow for the legitimisation of their involvement in other conflicts?

Women warriors have captivated broad European audiences as Italian and German female foreign fighters travelled to Syria to support the YPJ. Since 2013, around 200 people have travelled from Germany to fight alongside Kurdish forces in Syria and approximately 25 Italians fighters have officially joined the YPJ, aligning themselves with left-wing, communist or anarchist ideologies. Left-leaning parties in Germany also played a role in supporting the fight. “When young people from Germany, in full knowledge of the danger, take it upon themselves to participate in the fight against the Islamic State in Syria, then I have the greatest respect for that decision,” Ulla Jelpke from the leftwing German party Die Linke mentioned in April 2017.

The Civil War Paths project advocates for a change in mindset when studying conflict actors, emphasising the importance of emotions and radical ideologies. Edoardo Corradi argues that non-material factors play a significant role in motivating foreign fighters to join the YPJ in Syria. Nicola Mathieson also demonstrates that conflict legitimacy is rather based on ‘muddy social constructions of threat’. In this blog, I aim to encourage the investigation of ideological factors and argue that examining the role ideology plays for both states and their proxies will deepen our understandings of sponsorship relationships.

In a recent article, I examine sponsorship relationships in Syria based on strategic objectives, and show that ideology appears to persist in contemporary proxy wars. Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Iran’s participation in Syria’s proxy war supporting different proxy groups, illustrates their tendency to align with groups sharing similar ideologies while actively avoiding those that may pose a threat to their own ideologies as exemplified by Saudi Arabia’s avoidance of supporting the Muslim Brotherhood.

Women fighters: a not so new phenomenon

Women fighters in civil wars are not a new phenomenon, but their visibility in this role has increased only recently, while recognition for their skills in combat is still developing. Throughout the American Civil War (1861-1865), approximately 400 women participated, mostly disguised as male soldiers, in the ranks of the Confederacy and the Union. A newspaper piece of the time mentioned: “many women there were who shouldered the musket, rode until they dropped, and stood fire like a man.” During the Cold War, women fighters participated in civil wars without resorting to adopting a male disguise.

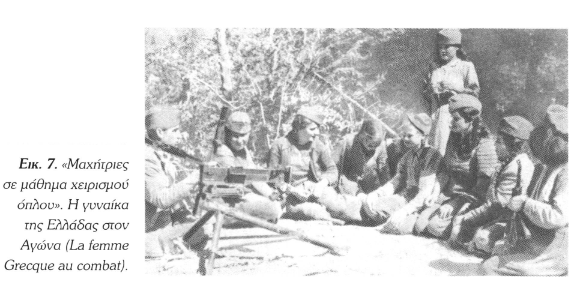

Recently, I came across an image vividly depicting Greek women fighters during the Greek Civil war (1946-1949). They are shown sitting in a circle, being instructed by a fellow combatant from the Democratic Army on how to operate a heavy machine gun. Women fighters also participate in contemporary conflicts, such as in Colombia, Ukraine, and elsewhere. Nonetheless, the assumption that a fighter is often male persists, reflecting society’s deeply gendered ideas about combatants. Susan Blackburn highlights this disparity, in this piece on Asia, that questions the ways in which Disarmament, Demobilisation, and Reintegration processes often overlook women warriors who fought in Cambodia and East Timor.

Yet, the presence of female fighters in Syria and elsewhere has led to numerous news articles, some exhibiting female fighters as the “most inspiring women of 2014” (CNN, 2014), others projecting essentialist ideas reporting “beautiful female fighter dubbed the Angelina Jolie of Kurdistan dies while battling ISIS in Syria” (The Sun, 2016). Many of these stories may reinforce Western audiences’ perceptions of the Middle East as a barbaric ‘Other’, reflecting Orientalist lenses rooted in colonialism and portraying an essentialised image of culturally inferior civilisations.

Indeed, the YPJ have been depicted as fighting against ISIS forces, which sought to enslave them. For example, the U.S Central Command, while providing training to YPJ forces, shared on X pictures of the women fighting in Kobani, noting that this was in response to “popular demand for more photos”. Gayle Lemmon, in a podcast discussing her book “The Daughters of Kobani”, which narrates the lives of these fighters, encapsulates popular feelings towards them as a “mixture of admiration, pride and even jealously over the women’s determination and courage” expressed by the U.S. Special Forces that train them.

Caption: pic. 7 “Women fighters taught how to handle a gun” The women of Greece in Battle. Source: Kassianou, Ν. (2006) ‘Γυναίκες στα όπλα: Η γυναίκα σε αναπαραστάσεις, η περίοδος του εμφυλίου πολέμου 1946-1949’, in Γραμματικοπούλου, Ε. and Βιγγοπούλου, Ι. (eds) Ήρωες και ανώνυμοι, αφανείς και επώνυμοι στις παρυφές της ιστορίας και της τέχνης. Εθνικό Ίδρυμα Ερευνών (Επιστήμης κοινωνία: Ειδικές μορφωτικές εκδηλώσεις), pp. 149–175. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10442/1760.

Ideology and proxy war: a new research agenda

Gender equality has been a central ideological trait of the Kurdish PYD (Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat, Democratic Union Party) to which the YPJ belongs. This ideological fight was largely positioned against ISIS’s misogynistic ideology, which became the reality for women in territories held by ISIS. Recent empirical research has also pointed to the role of gender framing in rebel efforts to secure support from other state and non-state actors. This aspect of gender framing was not lost on Assad either, as in 2015, pictures of women who were recently conscripted to the Syrian army coincided with Assad’s statements to the American television station CBS, expressing his openness to dialogue with the U.S.

European governments have supported Kurdish forces fighting ISIS both militarily and politically, enjoying broad support from their publics. For example, last September, the Foreign Minister of Luxembourg, Jean Asselborn, publicly expressed his condolences for the death of three Kurdish fighters in Syria, drawing attention to the ongoing clashes between Turkey and the Kurdish forces in Syria.

The question of the role that ideology plays in securing Western funding for conflict actors is salient in conflict studies. Women fighters are neither a new nor waning phenomenon in civil wars, and their material and ideological contributions to armed groups is received positively by Western states who continue to play an important part in influencing proxy civil wars, as evidenced in this piece. Consequently, attention to the role of gender framing by conflict actors offers significant opportunities to deepen understandings of when, how and why Western states endorse, support and finance armed groups.