Michael Kriner

“there remain instances where peacekeepers have either failed to protect civilians from violence or have directly engaged in violence against civilians.”

Since 1999, all multi-dimensional United Nations (UN) peace operations have included a mandate to protect civilians. In the midst or wake of violent conflict, UN peacekeepers are tasked with a host of objectives to help make, keep, or build peace in mission host countries. While missions are involved with election assistance, security sector reform, and rebuilding government institutions, they are often judged by their ability to protect civilians from abuse and violence. This priority area has become a particular focus of the UN following the ‘robust’ turn in UN peacekeeping, and features in the commitment areas of the Secretary General’s Action for Peacekeeping (A4P) initiative. As a critical area for the UN, it is vital to understand the conditions that lead peacekeepers to effectively engage in civilian protection.

In this blog post, I contribute to the theme of ‘building bridges’ by linking research to practice on UN civilian protection. Drawing on work for my dissertation, I highlight how domestic politics in countries that contribute to UN peace operations impact peacekeepers’ ability to effectively provide protection for civilians. Here, I focus on the ways in which security forces (police and military) are trained and utilised in their home countries, and how this translates to performance when deployed to UN peace operations.

The UN and Civilian Protection

Deployed to difficult contexts, peacekeepers arrive in mission host countries needing to establish relationships with local actors. Creating bonds with civilians is paramount for peacekeepers to be able to help civilians. By their presence, peacekeepers can deter violence against civilians by raising the costs of targeting civilians and by acting as a physical barrier between peacekeepers and would-be belligerents. Academic research into the UN’s ability to protect civilians suggests that peacekeepers are, in general, able to do so.

Yet there remain instances where peacekeepers have either failed to protect civilians from violence or have directly engaged in violence against civilians. Additionally, though the UN maintains a ‘zero tolerance’ policy for sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) by peacekeepers, peacekeepers continue to engage in SEA. In the Central African Republic, Mauritanian peacekeepers, part of the UN’s MINUSCA mission, came under scrutiny for their actions leading up to, and possible inaction during, an attack against an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp in Alindao in November 2018. Reports suggest that peacekeepers tasked with protecting the camp failed to tamp down on rebel group elements within the site, creating an environment conducive to violence and crime. In doing so, peacekeepers had lost the trust of those they were meant to protect.

Peacekeeper Backgrounds and Deployment

The tragic example of the Alindao IDP camp attack exemplifies the connection between domestic politics and UN peace operations’ ability to effectively protect civilians in mission contexts. In my research, I unpack these domestic politics by focusing on the differences in peacekeeper backgrounds as either autocratic or democratic and argue that peacekeeping deployment externalises the training, tactics, and strategies that security forces use domestically to peace operation host countries. Autocracies are, generally, characterised by the tendency to use security forces in instrumental ways to ensure leader and/or institutional survival, while democracies often include civilian oversight of security forces. These differences significantly shape the interactions and relationship between civilians and security forces that creates a permissive environment for civilian violence in autocracies and a system of accountability in democracies.

For example, though Mauritania has elections, the country has been led by a series of military leaders and, even when out of power, the military has maintained a stronghold on politics, staging a coup in 2008, following the country’s first democratic elections in 2007. Despite being abolished in 1981 and criminalised in 2007, human trafficking and slavery remain issues in Mauritania, as does repression and discrimination against human rights activists, opposition groups, and Black Mauritanians. The military in Mauritania have participated in repression that has left the aforementioned legacies.

In 2021, Gabonese peacekeepers were repatriated from the MINUSCA mission following numerous allegations of SEA. Recently, in 2023,, Gabon experienced a military coup, following a spate of coups in western Africa, demonstrating that the military remains an important institution of power and abuse. The risks of externalising domestic practices of repression by security forces from autocratic contexts has been recognised by the international community. For example, calls have been made for the UN to ban members of Bangladesh’s Rapid Action Battalion from UN mission deployment which has been accused of engaging in abuse and human rights violations domestically. These instances highlight the tense environment for civil-security force relations in autocracies both domestically and when deployed in missions, where the latter view civilians as a population to be protected against rather than providing protection for.

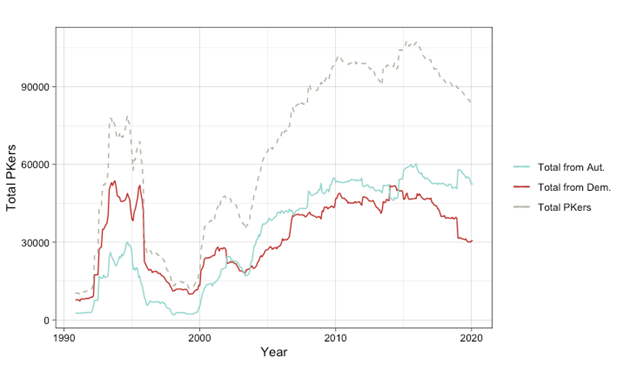

The focus on autocracies and their security forces is additionally important given the increasing participation of autocracies in UN peace operations. The figure below visualises peacekeeping contributions from democracies and autocracies from 1990-2020. While peacekeeping missions in the early post-Cold War period were predominantly composed of peacekeepers from democratic countries, since the early 2000s, peacekeepers are increasingly provided by autocratic contributors. This increase has had, and may continue to have, negative implications for the UN’s ability to protect civilians from harm.

Though we are just beginning to explore the effects of increased participation of autocracies in UN peace operations, the current trends warrant our further attention. The examples of Mauritania, Gabon, and Bangladesh signal that there may be a mismatch between the aims of UN peacekeeping and the personnel deployed to carry out these missions. Yet, it is also important to recognise that security forces from democracies also engage in abuse and violence when deployed abroad as exemplified by accusations of sexual abuse by French peacekeepers in CAR and violence committed by Canadian peacekeepers in Somalia. This suggests the need for further research on domestic politics in contributing countries to highlight additional factors that may contribute to better civilian protection. The role of ‘personal identities’ as articulated recently by Tom Buitelaar in his call to bring humans back into the study of peace and war may also offer new avenues through which to expand knowledge on peacekeeper behaviour. To improve peacekeeper performance, we ultimately need to look to, and beyond, differences between autocracies and democracies to uncover why peacekeepers from a variety of backgrounds engage in abuse and/or fail to protect civilians.