Federico Manfredi Firmian

‘The international community – and the United States in particular – should stand behind reformist voices, by putting pressure on state authorities to stop violent crackdowns and act responsibly in response to peaceful demands for change. Failure to act now will only exacerbate Iraq’s multifaceted problems, and make it more difficult to reverse the series of negative trends that have come to pose an existential threat to its people…’

Political unrest has Iraq on edge. The power struggle pitting Moqtada Al-Sadr against the Iran-backed Coordination Framework parties and their militias has already left over 30 people dead in the Iraqi capital in August, and some now fear that a civil war within the Shia community could break out at any time. Meanwhile, popular demonstrations marking the third anniversary of the Tishreen (October) movement of 2019 are once again challenging the government over its corruption and ineffectiveness, despite the security forces’ history of brutal crackdowns.

The latest political troubles are but a symptom of deeper problems. Iraq is facing a slow-burning descent into chaos, and not just as a result of militia leaders jostling for power, but rather due to a series of systemic challenges of monumental proportions. The elephant in the room may well be Iraq’s highly dysfunctional political system, but global climate change and dam construction in neighbouring Turkey and Iran are likewise driving environmental and societal breakdown, and contributing to push Iraq ever closer to the brink state collapse.

This piece engages several of the pillars of the UN’s ‘Sustaining Peace’ programme, around which the Civil War Paths blog series is structured. In particular, it highlights how theories of change and conflict resolution may fall short in the real world, as in the case of consociationalism in Iraq; it also speaks to the need to change mindsets, shifting away from a focus on short-term fixes, such as government formation and compromises between political elites, towards medium- to long-term sustainable peace outcomes.

The perils of consociationalism

Iraq owes its current political system to the United States, which helped to institutionalise it during the 2003-2005 transition. It is a textbook case of what political scientist Arend Lijphart called consociationalism. I.e. a political system featuring power sharing mechanisms aimed at striking a balance between distinct social segments, in this case Shia Arabs, Sunni Arabs, and Kurds. Ethno-sectarian consociationalism, however, is problematic, as Toby Dodge noted in a poignant critique of Iraq’s institutions. First of all, ethno-sectarian consociationalism incentivises political parties and their leaders to pursue the narrow self-interests of their ethno-sectarian base, rather than the interests of society at large. Iraqis who have no inclination to vote based on ethno-sectarian affiliation, meanwhile, find themselves politically marginalised. To make matters worse, the Iraqi political system also features built-in mechanisms designed to promote consensus, which invariably result in policy gridlock, as competing ethno-sectarian interests tend to render the search for political compromise lengthy and elusive.

Iraq’s notorious corruption is also a product of ethno-sectarian consociationalism. In the absence of consensus on major policy questions, Iraq’s political parties long focused on obtaining public sector jobs and funds, in shares roughly proportional to their electoral performance (although parties with powerful militias generally managed to extract somewhat more than their fair share). Such dynamics fostered the emergence of what former finance minister Ali Allawi recently called ‘a vast octopus of corruption and deceit’. They are also responsible for Iraq’s ministries being filled with party cadres with ‘no meaningful experience or language skills, and with little understanding of modern practices in public administration’, Allawi said.

Popular demands for change meet repression and constitutional hurdles

The people of Iraq did try to reform the system. In October 2019, tens of thousands gathered in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square and for months on end they protested the sectarianism and corruption of Iraq’s public institutions, as well as the preponderance of militias in Iraq’s political life. The security apparatus responded with overwhelming force, employing live fire to disperse the protests, at the behest of the same Iran-backed militias that today stand behind the Coordination Framework. The Tishreen movement nonetheless succeeded in forcing the prime minister to step down, ushering in a new technocratic government, under the savvy leadership of Mustapha Al-Kadhimi.

The Coordination Framework parties and their militias, however, sought to block Al-Kadhimi’s reformist agenda, employing both formal and informal channels of political influence. And for one whole year after the October 2021 parliamentary elections, the Coordination Framework stonewalled government formation negotiations, until it secured the appointment of its preferred candidate as prime minister, in October 2022. That the Coordination Framework eventually got its way, despite a poor electoral performance, plainly reveals the failings of a system based on ethno-sectarian power-sharing and the elusive search for political consensus.

The collapse of agricultural communities and the growing risk of state failure

Meanwhile, Iraq is slowly but inexorably falling apart. Policy gridlock blocks the passing of the budget and other essential policy actions. Public infrastructure is crumbling. And agricultural communities and once vibrant natural ecosystems are collapsing, often irretrievably.

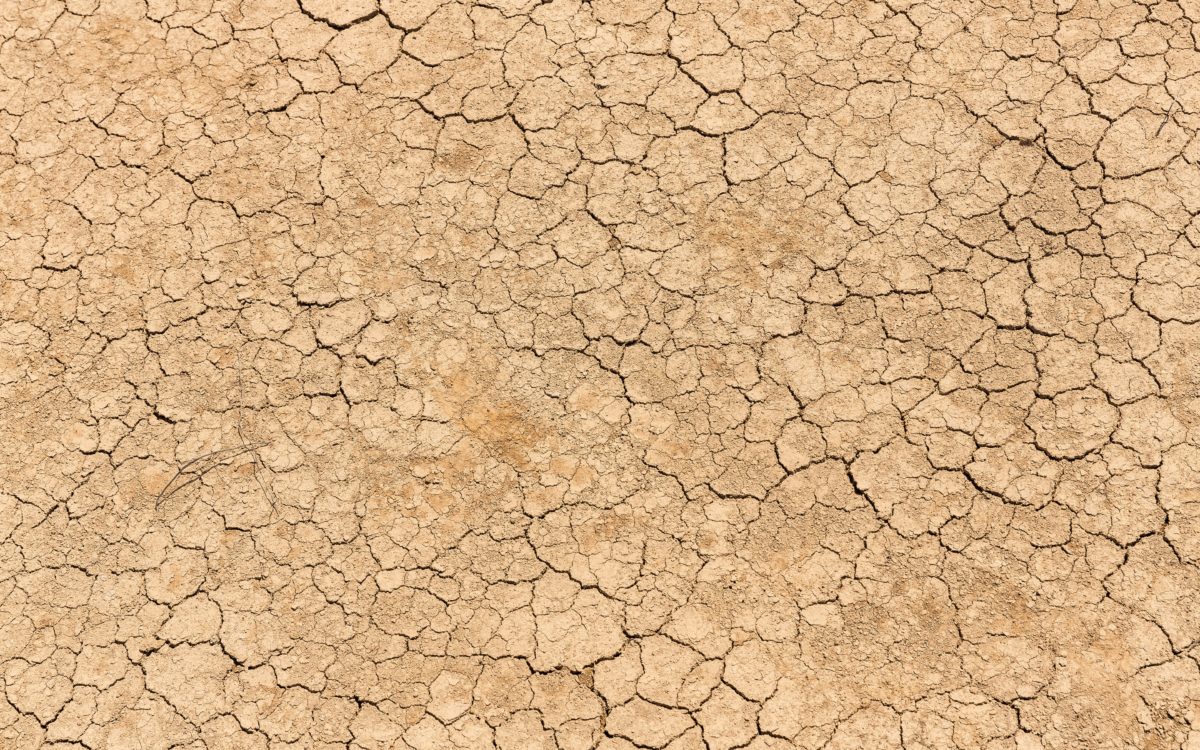

Iraq is the fifth most vulnerable country to climate change, according to the United Nations, and more frequent and intense droughts are contributing to crop failures and desertification, ravaging some of the poorest and most marginalised agricultural communities in the country. The construction of dams in Turkey and Iran has likewise reduced the water flow of the Tigris-Euphrates River Basin. As a result, the salty waters of the Persian Gulf now creep some 85 miles into the waterways of southern Iraq, killing off palm trees and other cash crops, and causing livestock to starve. Pollution – in particular the discharge of raw sewage in Iraq’s waterways – only adds to the crisis: killing off fish populations, poisoning crops, and destroying the livelihoods of poor rural communities.

Large numbers of Iraqis are abandoning the countryside and moving to overcrowded urban slums and shantytowns, in search of better lives. But there they face high unemployment, crime, and the hostility of local residents, who often blame climate migrants for pubic service congestion. Local politicians often fan tensions, so as to distract the public from their own failures. Armed groups, on the other hand, view desperate populations as ready reservoirs of recruitment. ISIS long sought to enlist poor farmers who lost their livelihoods due to climate change. Shia militias are likewise recruiting destitute young men. The shantytowns and newly built slums of Baghdad, Basra, and other cities often bear the flags and insignia of different militias, which signal a community’s affiliation, in a mafia-style racket of protection and exploitation.

The unforgiving road ahead

Neither a political deal between Sadr and the Coordination Framework nor a new round of elections will solve Iraq’s multiple crises. Indeed, what Iraq needs is a thorough overhaul of its political system, as the Tishreen protesters long demanded. Yet, police and military repression and militia violence stand in the way, as do constitutional hurdles and political elites eager to protect their privileges.

The international community – and the United States in particular – should stand behind reformist voices, by putting pressure on state authorities to stop violent crackdowns and act responsibly in response to peaceful demands for change. Failure to act now will only exacerbate Iraq’s multifaceted problems, and make it more difficult to reverse the series of negative trends that have come to pose an existential threat to its people.