Anastasia Shesterinina

‘Overall, the panels highlighted different ways in which we can view civil war as a process as well as different dynamics, factors and actors which are central to civil war’

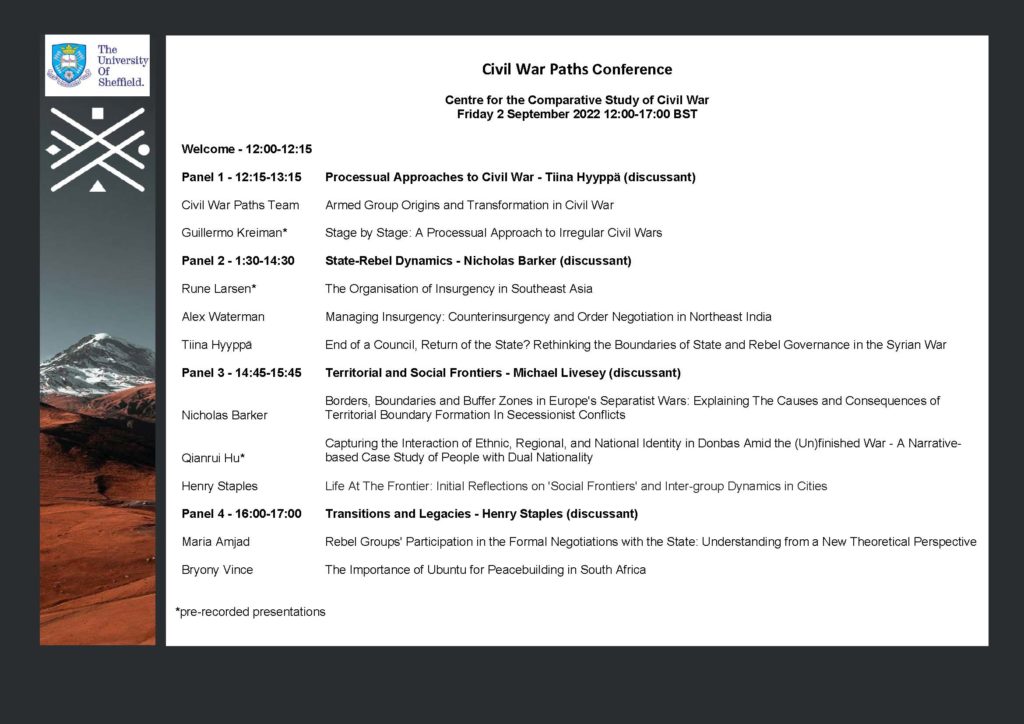

On 2 September 2022, the first virtual Civil War Paths Conference brought together over 50 participants to discuss cutting-edge research on a range of topics related to civil war. Presenters and discussants from among the Civil War Paths research team and 2021-2022 Fellows of the Centre for the Comparative Study of Civil War led the five-hour marathon showcasing 10 works in progress, including papers, book projects and grant proposals, in four stimulating panels. Attendees ranged from the outgoing and incoming cohorts of Fellows to scholars and practitioners within the broader community of the Centre and members of our Advisory Board.

Themes

Following introductory remarks on the approach to civil war as a social process developed as part of the Civil War Paths project, the opening panel on Processual Approaches to Civil War delved into different ways in which civil wars can be viewed in processual terms. Anastasia Shesterinina and Michael Livesey in “Armed Group Origins and Transformation in Civil War” and Guillermo Kreiman in “Stage by Stage: A Processual Approach to Irregular Civil Wars” asked how armed groups emerge in different ways and what pathways they follow. Starting with a common question, speakers offered distinct yet complementary answers. Shesterinina and Livesey focused on membership and activities of armed groups and identified their clandestine, social movement and state splinter origins. They argued that these origins condition armed groups’ initial relations but that these groups transform through endogenous dynamics of civil war, with examples from fieldwork in Nepal and Lebanon offered by Hanna Ketola and Toni Rouhana, respectively. In turn, Kreiman zoomed into the stages of civil war in relation to insurgent strength and found that this approach can help understand transformation from marginal to successful armed groups, particularly in Latin America.

In direct conversation with these approaches, the panel on State-Rebel Dynamics opened with Rune Larsen’s “The Organisation of Insurgency in Southeast Asia.” Larsen drew our attention to insurgent endowments as mediating between different origins and pathways of armed groups, asking whether these concepts are distinct or constituent of a broader conceptual framework. By looking at how states grapple with and manage different forms of “order” that emerge in civil wars, Alex Waterman further problematised processual approaches to civil war in “Managing Insurgency: Counterinsurgency and Order Negotiation in Northeast India.” This discussion raised important questions about the role of the state in armed group trajectories. Bringing to bear insights from field research on the Syrian war, Tiina Hyyppä extended this discussion in “End of a Council, Return of the State? Rethinking the Boundaries of State and Rebel Governance in the Syrian War.” Hyyppä asked how hybrid governance is organised and argued against geographically bounded understandings of such governance with a focus on sub-state actors.

These and other boundaries were at the heart of the next panel on Territorial and Social Frontiers. Nicholas Barker launched the panel exploring how political maps are destabilised and reshaped by separatist wars. Barker’s “Borders, Boundaries and Buffer Zones in Europe’s Separatist Wars: Explaining The Causes and Consequences of Territorial Boundary Formation In Secessionist Conflicts” was a powerful reminder about the impact of demarcations of territorial control on conflict and cooperation outcomes. Qianrui Hu shifted the focus from territorial to social boundaries. “Capturing the Interaction of Ethnic, Regional, and National Identity in Donbas Amid the (Un)finished War – A Narrative-based Case Study of People with Dual Nationality” stressed the need to move away from common categories such as ethnic identity that do not capture the situational fluidity of identities in conflict settings. Henry Staples drew links between social and spatial boundaries in “Initial Reflections on ‘Social Frontiers’ and Inter-group Dynamics in Cities” based on neighborhood-level data from the broader project “Life At The Frontier.”

How are peace processes set in motion in the context of such complexity? And what underlying norms and understandings underpin these processes? These were the questions guiding the final panel on Transitions and Legacies. Focusing on the case of US-Taliban talks from February 2020 to August 2021, Maria Amjad observed that while some armed groups maintain their commitment to formal negotiations, others back out. “Rebel Groups’ Participation in the Formal Negotiations with the State: Understanding from a New Theoretical Perspective” proposed that viewing negotiations as political processes that do not follow linear stages can help understand this variation. Last but not least, Bryony Vince in “The Importance of Ubuntu for Peacebuilding in South Africa” demonstrated that “indigenous concepts” such as Ubuntu need to be carefully examined in order to understand their effect on peacebuilding. Vince relied on four months of field research in Cape Town to call for greater nuance in discussing “local” approaches to conflict resolution as NGOs, community organisations and individuals draw on local knowledge in different ways in conflict resolution.

Directions

Overall, the panels highlighted different ways in which we can view civil war as a process as well as different dynamics, factors and actors which are central to civil war. Some presentations suggested the utility of a staged approach for our understanding of armed group evolution (Kreiman), whereas others emphasised the interconnectedness and nonlinearity of stages, for example, in peace negotiations (Amjad). Some focused on membership and activities of armed groups to make sense of their initial internal and external relations (Shesterinina and Livesey), whereas others on these groups’ endowments in combination with their origins and pathways (Larsen). Some drew attention to the role of central state actors in the evolution of “orders” in civil wars (Waterman), whereas others on sub-state actors such as local councils (Hyyppä). Territorial (Barker) and social (Staples) boundaries along with shared identities (Hu) and understandings (Vince) were an underlying thread throughout these dynamics. These themes point to fruitful directions in future research on civil war, with works in progress presented at the conference making important contributions to debates on these and other questions.