Michael Livesey

“No significant civil war dynamic ever appears in isolation from its historical formations… Past and present are always interpellated.”

The Civil War Paths project sets out to explore processes by which intrastate conflicts unfold. The project identifies three ‘stages’ of a civil war process: pre-war, war, and post-war. But some questions remain as to how we should operationalise these stages. How long is each stage, for instance? How far back in time should we trace a conflict’s ‘pre-war’ origins? How far forward in time should we travel to assess ‘post-war’ dynamics? And how do we situate the short-time processes of the war itself, within their longer-time historical durée?

Political science and international relations scholarships tend to operate narrow temporal horizons: both in terms of their imbalance towards analysing present dynamics (their ‘fraught’ or ‘amnesiac’ relationship with anything older than a decade or so); and their tendency to assess events in their immediate micro-contexts (failing to situate such events within their long-term histories). This siloisation of past and present is a problem. It risks isolating present dynamics from deep-rooted temporal contexts – limiting our understanding of immediate ‘micro-processes’, by divorcing these from ‘macro-processes’ out of which they emerge.

This blog contributes to questions of civil war ‘process’ by flagging the need to situate conflict dynamics according to their longue durée. It notes findings from my recent publication in the European Journal of International Security: demonstrating 1970s British counter-terrorism in Northern Ireland’s emergence from a long-term history of Anglo-Irish relations. This publication explores the interface between language the UK Government used to legitimise Britain’s turn to ‘exceptional’ domestic security (as a way of containing so-called ‘Troubles’ violence), and established traditions of British discourse on Northern Ireland. It shows how present ‘processes’ (1970s securitisation) overlap with past inheritances (norms which made that securitisation possible).

Macro-processes: British discourse on Northern Ireland, 1920-1984

My research is based on a quantitative analysis of all UK parliamentary debates on Northern Ireland in the period 1920-1984. This is the period between Northern Ireland’s ‘emergence’ (its creation through north/south partition on the island of Ireland); and its 1970s ‘emergency’ (the outbreak of Troubles violence, after 1969).

In this research, I’ve found that the language according to which British political actors spoke about Northern Ireland across its first seven decades was remarkably consistent. Whenever debating Northern Irish questions, from ‘emergence’ to ‘emergency’, British political agents returned to a consistent vocabulary of concepts. These concepts included the notion of ‘the Northern Ireland problem’ requiring ‘solution’. Or, of a permanent ‘Northern Irish emergency’ (a contradiction in terms, given emergencies are, by definition, temporary – but a configuration which nonetheless appeared in stable quantities across many decades of discourse).

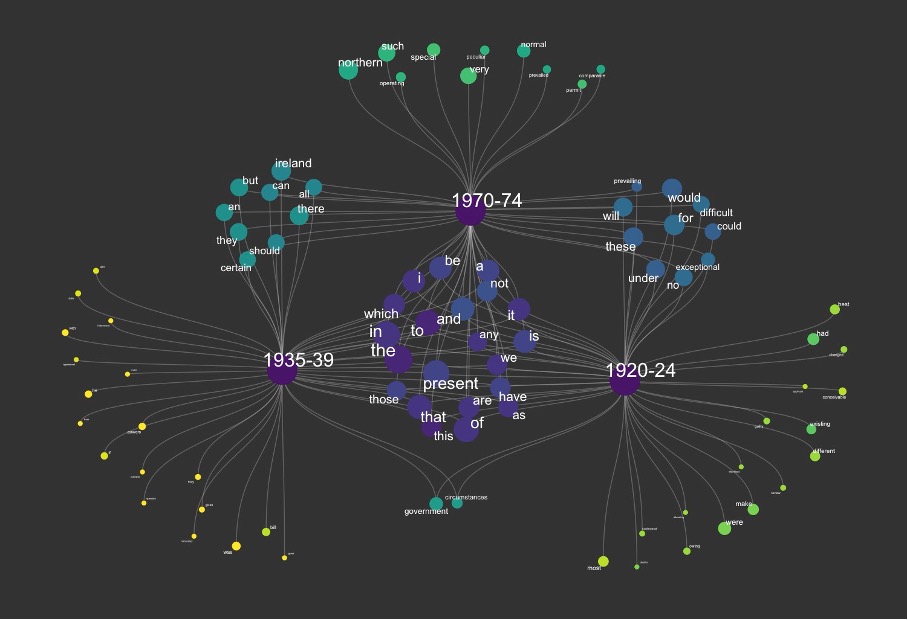

I show this continuity of language in the network graph below. The graph shows all words appearing alongside ‘emergency’, in parliamentary debates on Northern Ireland from three different periods of the twentieth century (the 1920s, 1930s, and 1970s)

This graph clarifies the stability of a system of rules for speaking about Northern Ireland in British political discourse. It notes the proliferation of patterns for discussing Northern Ireland across multi-decade periods – as signified by the re-appearance of ‘the emergency’ according to a consistent linguistic profile, in each period.

Many things changed between the three decades in this graph – including who spoke in parliamentary debates, and what those people discussed (the questions they faced, and the conditions in which they interacted). Yet, the language by which MPs conceptualised Northern Irish affairs remained consistent. In my article, I describe this continuous language as a ‘conceptual archive’: a stable system of ‘rules’ or ‘norms’ for debating Northern Ireland.

Micro-processes: 1970s securitisation

When the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles’ first broke out, the British Government sought new domestic security powers to contain paramilitary violence. These powers crystallised in two pieces of 1970s legislation: the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1973 (EPA), and Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act 1974 (PTA).

Within the micro-process of the Troubles, these laws represented a significant transformation. They shifted the balance of power over violence in favour of state security, and away from paramilitaries, by enabling detention without charge for paramilitary suspects; non-jury courts for paramilitary trials; reductions in the onus of proof for prosecution; and executive exclusion for suspected ‘terrorists’. EPA/PTA tipped the scales of conflict in favour of containing paramilitarism (with Northern Ireland’s non-jury court system, for example, enjoying a very high 80% conviction rate vis-à-vis mainland jury courts).

As an endogenous dynamic of conflict processes, EPA/PTA’s emergence is an important part of the analytical picture. However, this shift in Troubles micro-processes did not appear out of the blue, in isolation from longer-term patterns. On the contrary, the EPA/PTA micro-pivot within conflict processes must be understood in relation to historical macro-contexts.

Legitimising counter-terrorism: the ‘conceptual archive’

The most important thing to note about this macro-context is the interface between new Government powers designed to contain Troubles violence, and the system of norms for speaking about Northern Ireland set out above.

The new laws Government proposed to empower state security were not guaranteed to pass Britain’s legislative processes. On the contrary, when Government first introduced EPA/PTA to parliamentary legislators, these laws were rejected as being at odds with Britain’s supposed tradition of liberal domestic security.

1970s counter-terrorism laws aroused animosity amongst legislators. EPA, for example, came up against 22 amendment divisions at parliamentary committee stage; whilst PTA saw fully 54 divisions. As a point of comparison, the highly-controversial EU Withdrawal Act 2020 suffered only twelve committee divisions; and the Coronavirus Act 2020 encountered none.

EPA/PTA’s unpopularity amongst parliamentarians raised Government actors’ awareness to the requirement for a careful strategy by which to ‘stage manage’ new powers’ legitimation. And central to this strategy was an effort to frame EPA/PTA’s legitimacy in a language already enjoying purchase in parliamentary discourse. This was the language of my ‘conceptual archive’.

Government’s argument in favour of EPA/PTA’s legitimacy took shape according to parameters which were already familiar to legislators – parameters the latter had become habituated to, over decades of debating Northern Ireland. In legitimising ‘exceptional’ domestic securitisation, Government speakers resorted to an ‘accepted’ language of concepts; including, for example, the language of Northern Ireland’s ‘present emergency’: operationalising familiar assumptions about Northern Ireland’s ‘emergency circumstances’ to justify powers as ‘temporary’ (and not a challenge to ‘permanent’ liberal norms).

This elision between ‘exceptional’ measures and ‘accepted’ discourses lubricated EPA/PTA’s passage through Parliament. Government actors sustained this transformation in domestic security practice through conformity with multi-generational patterns of discourse: cutting their arguments for new practices from an established conceptual fabric.

Micro-processes, macro-histories

This finding is important. It reveals that transformations in a war’s unfolding never emerge overnight. On the contrary, these transformations are situated in patterns of action with histories of their own. Counter-terrorism’s emergence in 1970s Britain would not have been possible without the UK Government’s careful rhetorical strategy legitimising domestic securitisation. Such legitimisation in the present moment of action, moreover, worked in communication with discursive norms handed down from a long-term past.

Whenever assessing a civil war’s unfolding, we must always take endogenous transformations into account. But we must also note ways these transformations fit into macro-processes of action and interaction. No significant civil war dynamic ever appears in isolation from its historical formations. Rather, such dynamics always exist in relation to the longue durée. Past and present are always interpellated.

Our analyses of civil war processes cannot be restricted merely to the short ‘window’ in which a conflict itself takes place. Instead, we must always keep an eye on the interface between ‘micro’ process of war, and ‘macro’ processes of history.