Mark Berlin

@mark_berlin2

“Talk, when it comes to armed groups, is far from cheap.”

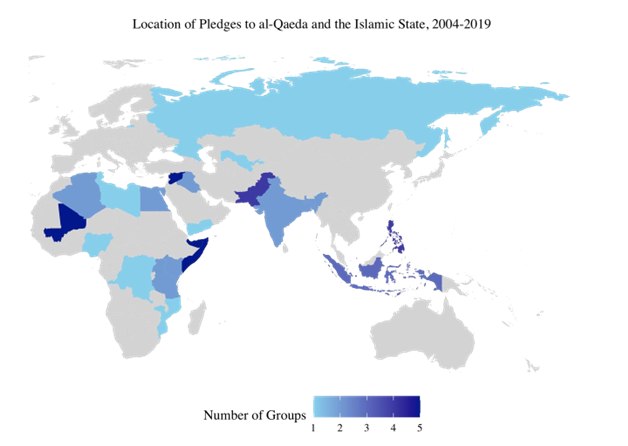

In recent years, dozens of jihadist groups pledged allegiance (bay’a) to al–Qaeda and the Islamic State. To date, however, pledges of fealty and other forms of rhetorical cooperation among armed groups remain understudied in political violence research on militant cooperation. Cast aside, discursive acts are often thought of as occupying the ‘lowest level’ of cooperation, as the formation of militant alliances supposedly ‘requires meaningful interaction as opposed to mere verbal support or ideological affinity.’

This post contributes to the Civil War Paths’ ‘Building Bridges’ blog series in multiple ways: I detail the characteristics of rhetorical cooperation; why this form of collaboration matters for armed groups; and the need to examine the relationship between militant leaders and inter-organisational alliances. In doing so, I share findings from my doctoral research on militant cooperation and introduce a typology of individuals who act as key drivers of rhetorical cooperation among armed groups. Due to the influence of militant cooperation on the direction of civil wars across multiple regions, understanding the causes and consequences of armed group collaboration presents a pressing concern for both scholars and policymakers.

Understanding Rhetorical Cooperation

Rather than operate in isolation, armed actors cooperate (as well as compete) within and across borders in multifaceted ways. Numerous militant organisations have exchanged finances, propaganda support, tactical knowledge, training, and other material resources over recent decades. Armed groups also cooperate operationally, helping to plan and execute contentious actions against shared targets. In April 2012, for example, around 150 militants from the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan launched a joint operation against the Bannu Prison in Pakistan, freeing 384 prisoners.

Rhetorical cooperation occurs when an armed group discursively expresses support for another organisation’s behaviour, goals, or legitimacy. As with other forms of collaboration, the qualitative strength of rhetorical cooperation may vary, ranging from expressions of broad solidarity and the signing of manifestos to formal oaths of allegiance. Mirroring jihadist groups, for example, European branches of the white supremacist Atomwaffen Division pledged allegiance to the U.S.-based Atomwaffen group. More recently, various organisations, ranging from al–Qaeda to Hizb ut–Tahrir, issued rhetorical statements of support for Hamas and its attacks in Israel.

Why Rhetorical Cooperation Matters

Talk, when it comes to armed groups, is far from cheap. Through rhetorical cooperation, armed groups may create costly commitments. Take the case of pledges of allegiance given by jihadist groups to al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. This oath of allegiance forms a binding contract that is based on reciprocal duties. Breaking the obligations associated with this pledge can generate reputational costs, seriously damaging a leader and group’s standing in the jihadist movement. Hayat Tahrir al-Sham in Syria faced fierce criticism from prominent jihadists in 2017 over claims that it illegitimately broke its oath of fealty to Ayman al-Zawahiri.

Moreover, rhetorical cooperation also generates significant organisational costs. As a recent

International Organization article stated, rhetorical ‘relationships cannot be dismissed as cheap signalling because they present meaningful risks to security, reputation, and internal cohesion for the organizations involved.’ For example, the United Kingdom recently labelled Hizb ut-Tahrir as a ‘terrorist’ group due, in part, to its recent statements of support for Hamas.

Finally, rhetorical cooperation may also affect organizational identities and tactical choices. Numerous groups that pledged fealty to the Islamic State emulated its patterns of violence by beheading hostages. For its part, the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat introduced suicide bombings to its repertoires of violence only months after pledging allegiance to al-Qaeda and changing its name to al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). Due to its costs and impact on organisational behaviour, further research is needed to explain the causes and consequences of rhetorical cooperation among militant groups.

The Drivers of Rhetorical Cooperation

Scholars have pointed to multiple factors, such as shared ideology, power, and territorial control, that drive why and with whom armed groups cooperate. While providing critical insight into the behaviour of armed actors, existing theories primarily privilege organisational-level explanations, with theories that examine the importance of individuals to armed group behaviour remaining relatively understudied. However, rebel leaders, ranging from Abimael Guzmán and Shoko Asahara to Osama bin Laden, play a critical role in guiding organisational strategies, tactics, and external relations. For example, internal organisational documents underscore that al-Qaeda’s leaders expressed dismay at al-Qaeda in Iraq’s targeting of Shi’a and beheading of captives under the leadership of Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi. Despite ideological and tactical disagreements, al-Zarqawi did not disavow his pledge of allegiance, remaining within al-Qaeda’s orbit until his death in June 2006.

Examining pledges of fealty to al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, my research finds that two types of individuals are key drivers of this high-level form of rhetorical cooperation: new leaders and status-seeking subcommanders. First, in a similar fashion to new leaders of states, recently appointed armed group leaders face numerous challenges stemming from reputational deficits and inexperience when they take power. Following the arrest of Jamil Mukulu in 2015, for instance, Seka Musa Baluku faced internal misgivings over his recently acquired leadership of the Allied Democratic Forces. To overcome these obstacles, new leaders may engage in costly forms of behaviour like rhetorical cooperation. In doing so, these leaders can reduce uncertainty about their resolve, bolster internal support among factions that favour alliances with external groups, and augment their individual statuses.

Aside from top leaders, subcommanders also affect organisational behaviour and cohesion. Over time, subcommanders may become dissatisfied with their internal positions and disagree with their leaders’ stance on external relations. In response, these mid-ranking commanders may splinter and forge new alliances. Among jihadist groups, subcommanders may elevate their statuses in the jihadist movement by pledging fealty and, subsequently, taking control of high-ranking positions in al-Qaeda and Islamic State regional branches. Subcommanders have been particularly central to pledges of allegiance to the Islamic State. For instance, Abdelmalek Gouri, a former subcommander in AQIM, split from the al-Qaeda affiliate and pledged fealty to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in 2014, becoming the leader of the Islamic State’s Algeria Province. In another case, the Islamic State declared Isnilon Hapilon, a former subcommander in the Abu Sayyaf Group, as the regional emir of the Islamic State in Southeast Asia.

Conclusion

Conflicts are increasingly characterised by complex interactions between armed actors. Among such interactions, the employment of discourse remains a central way in which militant organisations cooperate. Understanding why armed groups engage in costly rhetorical acts and their effect on organisational identities, mobilisation efforts, and cohesion is critical for scholarship and policymaking surrounding civil war trajectories. Building on organisational-level theories, exploring the incentives for different types of leaders to collaborate with external groups in various ways offers a fruitful path for future research on militant cooperation. Aside from leadership tenure, analysing the biographical attributes of militant leaders, such as experiences fighting abroad, levels of education, and occupation, may shed further light on why individuals, and militant organisations more broadly, engage in certain forms of behaviour.