Anastasia Shesterinina

“The human side of being part of a large research project should not be taken for granted: It takes a culture of mutual support that requires consistent nurturing and care through practices developed at the individual and group levels.”

A year in review

During 2022-2023, the Civil War Paths team moved to the Department of Politics at the University of York, a major hub of conflict and peace studies with wide-ranging expertise on the subjects and cases that we explore in the project. I took up a Chair in Comparative Politics and doctoral and postdoctoral researchers have continued their work in this exciting new setting. While this was a complex transfer, we are grateful to the mentors, colleagues and support teams at the Universities of Sheffield and York who encouraged and made this milestone possible. In this context of change, the Civil War Paths team completed most fieldwork in Colombia, Lebanon, Nepal and South Sudan and presented early findings in academic and practitioner-oriented events, from the Civil War Paths panel at APSA 2022 to Geneva Peace Week 2022 to brown bag lunches and conferences in case study countries. The first case-specific publication on the project by Dr Hanna Ketola appeared in Civil Wars. We started identifying linkages between our field insights in team workshops on data analysis, interpretation and a co-authored book.

When back from fieldwork, we organized the First Civil War Paths Conference, which highlighted how our Fellows view civil war as a process in different ways. The Civil War Paths Seminar Series focused on our case study countries, bringing in conversation such esteemed experts as Pr Francisco Gutiérrez-Sanín who discussed the origins of pro-government militias in Colombia, Dr Heidi Riley who zoomed into insurgent masculinities in Nepal, Dr Peter Biar Ajak who problematized state formation in South Sudan, and Pr Sarah E. Parkinson who spoke about militant organizational adaptation in Lebanon. We were also fortunate to host Pr Lisa Wedeen who brought her unmatched knowledge of contemporary Syria to the discussion and joined our Advisory Board, and to engage in a thought-provoking dialogue on artistic and academic research and practice with our Advisory Board member Pr Duncan Higgins, art researcher Ivana Mančić and photographer Charles Fox.

Finally, we welcomed a new cohort to the Civil War Paths Fellowship Scheme. Our international, interdisciplinary Fellows shared their research on political leadership’s role in preventing violence, nonviolent resistance and repression in the context of environmental and societal breakdown, foreign fighters and volunteers in armed conflict, ‘war mentalities’ and ‘changing mindsets’, inclusion in peace processes and perspectives on justice, post-war military integration, female ex-combatants’ reintegration and broader institutional legacies of civil war, as well as on trauma in civil war research. These Civil War Paths blog contributions on the topic of Sustaining Peace (proposed by Michael Livesey whose time on the project came to an end last month) span contexts as diverse as Angola, Colombia, Iraq, Nepal, and the South Caucasus, creating meaningful connections with peacebuilding practice. We will maintain these and other forms of engagement with our Fellows, Advisory Board and invited experts as we move forward with the project, opening our Fellowship Scheme once again before the next Civil War Paths Conference, holding annual meetings and collaborating with the Advisory Board members and planning the 2023-2024 seminar series.

Humanity in team research

But another area of reflection deserves attention in this blog, that of the challenges we faced and will continue coming to terms with as a team. Russia’s war in Ukraine reverberated through our lives in significant ways. I was born and raised in Ukraine and have ties to both Ukraine and Russia. Seeing ordinary Ukrainians navigate unthinkable dilemmas as a result of the invasion hit through my core and painfully resonated with the research I conducted in the region. Other team members grew up with a sense of threat from Russia as a neighbouring state and saw similarities between Russia’s attacks on civilian infrastructure, including medical facilities, and destruction of Ukrainian cities in countries close to home, specifically Syria, where they conducted research. Uncertainty over what was to come struck us all. Yet we did not address what we were going through together, in part because our pain appeared to be irrelevant in the context of Ukrainian suffering and in part because what we were doing could never be enough. While the project continued running unaffected on the surface, this drew us apart on a personal level, and that level is particularly important for teams working on difficult and traumatic questions of war that require mutual support.

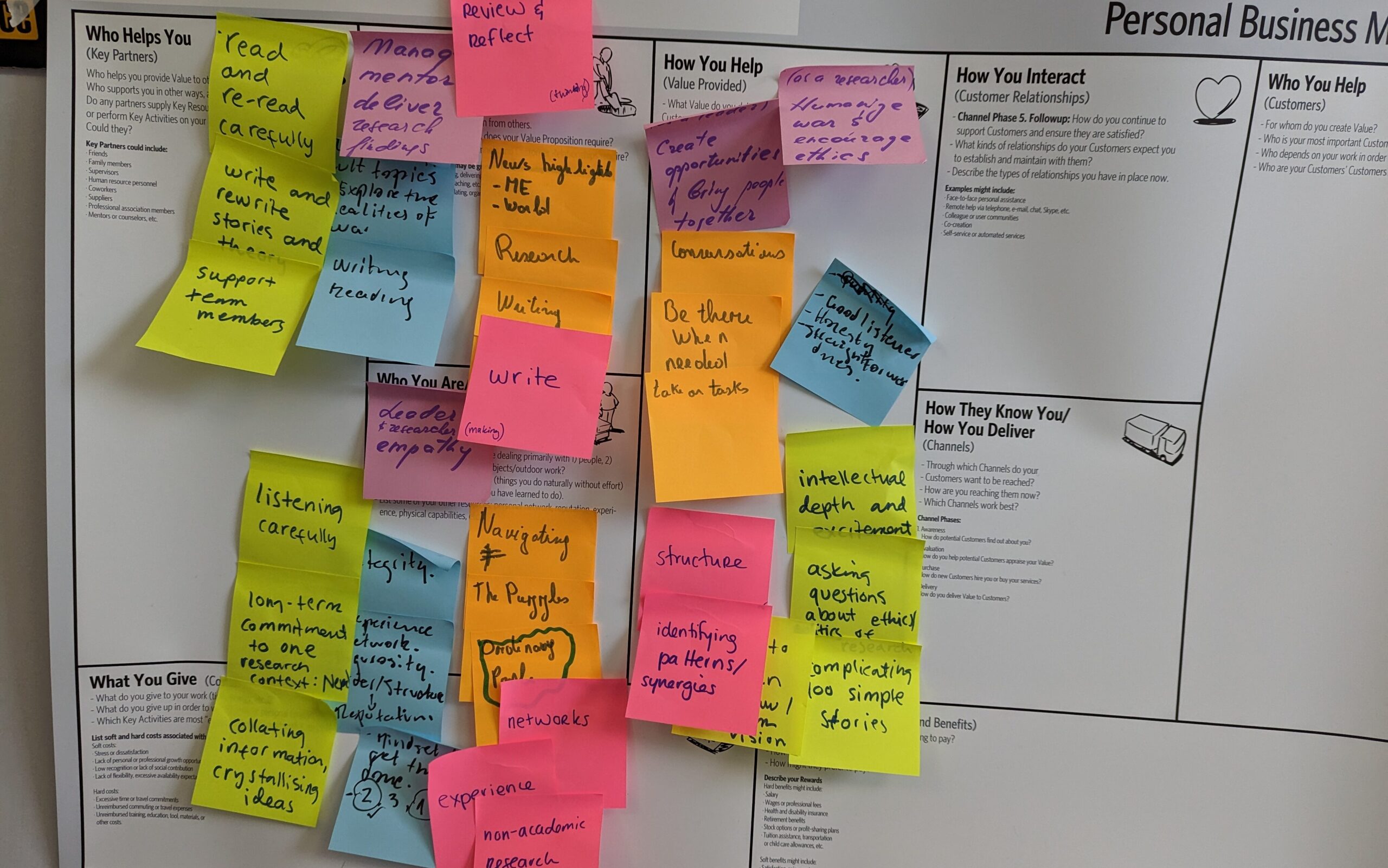

The personal slipped through the cracks for other reasons as well. Continued effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in the structure of the project intensified what one team member called the ‘crisis mode’ of the last year. Some team members struggled from isolation as much of our work took place virtually. We held team workshops, external presentations and only some seminars in person to facilitate online attendance by the Fellows. Constraints on those with families and whom COVID-19 left with long-term consequences for not only health but also livelihoods back home were especially high. As we negotiated new working arrangements, conversations we needed to have were delayed. They ultimately materialized because the approach we developed as a team prioritizes transparency, vulnerability and recognition of each other as human beings. And a frank discussion facilitated by Dr Sandrine Soubes at our away day in early 2023 untapped the struggles we had. This and further exchanges created a greater understanding of individual circumstances and expectations for our work as a team.

Nothing was more shattering, however, than the loss of my father at the end of 2022. This unexpected, life-changing event was not something that I could prepare or academia allows space for. My list of tasks and responsibilities was longer than ever, the time for bereavement was too short to even recover from the shock and I had never been good at saying ‘no’ or pushing deadlines. But the coming together of the team to take over the running of different parts of the project, offer each other help where it was needed and check in and ask me to slow down as I grieved gave me hope in the possibility of humanity even in the increasingly atomized and pressure-driven academic world.

This human side of being part of a large research project should not be taken for granted. On the one hand, it takes generosity of team members to be there for each other when confronted with personal and professional challenges in the research environment characterized by precarity. On the other hand, a culture of mutual support requires consistent nurturing and care through practices developed at the individual and group levels. There are necessarily breaks and shifts in this culture as in any social setting. But its maintenance is fundamental to our ways of being as research teams.